Some weeks ago, I was asked to review a paper for Lingua. Lingua is an Elsevier journal. A special one: five years ago the complete board of Lingua and the running editors resigned and recreated the journal with the new name Glossa. Glossa is published under the conditions of Fair Open Access. Since then there is no reason left to publish with Lingua and for me personally this means that there is no reason to publish with Elsevier.

Regarding the review, I wrote an email to the HPSG mailing list (HPSG stands for Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar, this is the framework I am working in). Maybe I overdid in stating that I will not hire anybody who publishes in Lingua. The discussion on the list was mainly about this aspect of my long email. However, I got replies in private and I want to comment on one of them, since I think that there may be other scholars with similar views, so it may be good to discuss them openly.

So here are the points of a good friend and colleague:

1. I still believe you do not realize that what you propose to do w.r.t. hiring amounts to “blacklisting” people because of their “political” views (which indeed people choose to adopt, but still it’s blacklisting to punish somebody’s employment opportunities because of her political views). Imagine Joann is a staunch capitalist who believes it’s the duty of publicly traded company to maximize profits (actually to some degree this is the executives’ fiduciary responsibility to shareholders) and that, although there is certainly excess pay and self-dealing among CEOs salaries, the best in the long run is to let the market take care of it (some version of Leibniz the best of all possible worlds). Joann also believes, correctly it turns out, that journals belong to the society or corporation that puts it out, so that Lingua is still an Elsevier journal even if the board and editors resigned (typical semantics of groups!), so there is no less reason to publish in Lingua than there is to publish in Cognition (another Elsevier journal). Joann might be wrong for you and most linguists, but what she does in submitting to Elsevier, Wiley, including Lingua, does not contravene any rule of any scientific society or any scientific code of conduct I know of. Punishing her for her behavior therefore does amount to punishing her for “political” views on publishing and that’s blacklisting in my book.

Yes, I fully agree with you that the job of the employees of for-profit publishers is to maximize profit and share-holder value. They are doing it and they do a good job. The problem that we see here is that the market is not doing its job. We have an oligopoly of the three big ones and we, the scientists, contribute to it. By transferring these large amounts of money to these publishers, we help them and enable them to grow. Name your favorite or disfavorite publishers and look where they ended up (We are collecting information about concentration in the publishing business). Buying these companies reduces the profit in the year when a publisher buys other publishers, but the remaining and growing publishers have profit rates above 37% even though they are growing.

The market is not doing its job and there have cases like this before: The US phone companies were split up and currently Facebook is sued in the US for buying Whatsapp and Instagram and just getting too big and (mis)using its power.

This is from Prof. Stuart Shieber’s piece, explaining why normal market mechanisms fail in the publishing business:

https://blogs.harvard.edu/pamphlet/2013/01/29/why-open-access-is-better-for-scholarly-societies/

Journal access is a complementary good

The first is that different journals — viewed as products, as goods being sold — are in economists’ terms complements, not substitutes. Substitute goods are products like Coke and Pepsi. If you have one it decreases the value of the other to you, as they fulfill similar functions. Complements are products like a left shoe and a right shoe – that’s the most extreme case. If you have one it increases the value to you of the other. There are less extreme cases of economic complements – printers and toner cartridges, peanut butter and jelly, pencils and erasers.

What about scholarly journals? Suppose you’re a patron of a library that subscribes to a bundle of, let’s say, Elsevier journals, including the journal Lingua. Does the library subscription to that journal make you more or less interested in reading, say, Language? (We’re holding cost aside. When thinking about complements or substitutes, it’s just about the value to the consumer, not the cost.) Of course, you’re not less inclined to read Language just because the library subscribes to Lingua. In fact you may be more inclined, because some Lingua articles will cite Language articles. You read the Lingua article, you want to to read the Language article it cites. So that would lead you to track down those articles and read them if the library had a subscription. And vice versa: a subscription to Language can increase the value of a subscription to Lingua. So journals are economic complements, not substitutes.

Inefficiency in the subscription market

This has important ramifications. Non-substitutive goods don’t compete against each other and complementary goods in fact support each other in the market. If consumers suddenly buy a lot more Coke, Pepsi is worried. But if peanut butter sales skyrocket, the jelly manufacturers are elated. So the complementary subscription of individual journals means that there’s limited market competition between journals, and limited competition leads to inefficiency in the journal market. (That’s not to say that there isn’t competition between publishers. But as we’ll see, the primary form of that competition is in competing to acquire journals.)

You said that publishing with for-profit publisher is not against any rules of the societies we are organized in. This is true in principle, but the DGfS distributed the suggestion not to publish in Lingua and not to work for Elsevier in its letter to the members in December 2015 (Nr. 82, p. 40):

A message from Waltraud Paul (former member of Lingua’s editorial board)

As of October 27, Lingua’s entire editorial team has resigned. This is our reaction to Elsevier’s refusal of the carefully prepared and fully financed change to a fair open access (OA) journal. Fair open access must be distinguished from so-called “Golden open access”, operated by Elsevier and other scientific publishers, where the author or her/his institution pay as much as 2000 euros to make their work accessible to non-subscribers.

Lingua’s former editorial team has the plan to found a new, fair open access journal called ‘Glossa: a journal of general linguistics’ on the platform https://www.openlibhums.org. Being run by the same scholars who have made of Lingua one of the leading journals in the field, this new journal will have the very same high quality standards. Contact details etc. concerning Glossa will be made public as soon as available. Glossa will officially be launched on 1st January, 2016 at Ubiquity Press and the Open Library of the Humanities, with the old team at the helm, and under conditions of Fair Open Access. Glossa will be included in the European Reference Index for the Humanities (ERIH-PLUS) as soon as the first issue is out (normal waiting time for new journals is 2 years).

You can express your solidarity with our initiative by signing the petition at: http://www.lingoa.eu/petition

In addition, we would like to ask you to spread the news, to stop submitting papers to Elsevier’s Lingua and to refuse any invitation to serve as a member of the new editorial board for Lingua which Elsevier will have to set up in the future.

(Note that the price for publishing an OA paper in 2015 was 2000€ and that it is now 2360€. This is an 18% increase. General consumer prices rose by 6% in Germany and by 10% in the US, so a happy app. 10% extra for Elsevier.)

In Germany, most university staff is directly payed by the state. There is external funding as well, but for the humanities this is mostly DFG, which is also state-financed and the European Research Council, which is also financed by the European countries. That is most university staff is tax-financed. If we want to buy a notebook, say, we have to get three offers from different sources and make sure that we buy the cheapest one. In general, state institutions have to be careful not to waste public money. There is an institution the Bundesrechnungshof that is checking such things.

Coming back to Joann: he may be a capitalist but he will be an uniformed one. Being informed about things like dysfunctional markets and about budgets and spending them responsibly is the duty of everybody working in Academia and being responsible for spending public money. People like Joann demonstrate their incompetence in this part of their job duties and hence there is a malus for hiring them. This is even more so since these things are discussed for some years now.

2. Publishing companies were critical to the development of science. Their role and place is in flux because of changes in technology, and there might come a time where they are not needed anymore (and I would personally welcome that day), but we are not there yet. Most journals are still published by corporations (broadly speaking) and if we were all to submit only to non-profit driven journals, there would be a serious lag in papers coming out (4 or 5 years; there is already too much of a lag) which is bad for science. Until there are enough non-profit journals of a high caliber, what you are proposing would hurt scientific dissemination (which is bad for science and bad for funding, for those who are in the grant business).

The main point of the mail was to not submit to Lingua. This is one journal and there is the perfect replacement for this one journal. So, nothing has changed in this regard.

Of course you are right, the general idea would be to transition all journals to Fair OA and if the publishers who own the brands do not do this, the editors should do this and found a fair equivalent to the non-fair original journal. At the moment a new fair OA journal replaces the old one, the old one turns into a Zombie and should no longer be supported.

Note that your view that the commercial publishers are needed since otherwise publication would be slowed down is wrong. What is needed to publish a paper nowadays? There is this quote in the OpenAccess scene: “Publish” is not a process, it is a button. All commercial publishers use online tools for reviewing and for online publication. Who is operating these tools? We are. The editor of the journal gets informed about a new submission by an author and passes the paper on to reviewers. The reviewers upload their review, authors revise and resubmit and eventually the editor clicks on publish. We do not need profit-oriented publishers for this. The software for this workflow (Open Journal System) is opensource and used successfully for example by the Journal of Language Modelling and also by the journal of the DGfS Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft (submission page using OJS). The bottleneck is in any case us: how long do the reviewers need for reviewing a paper? How much power / which skills does the editor have to make the reviewers deliver their reviews? We are living in a time in which everybody reviews everything, we are working on job search committees, grant committees, evaluating curricula, universities and so on. So who gets the review first? The most prestigious/the most pressing one. This has nothing to do with being commercial or not. (Side remark: Language may be a special case, they are thinking in volumes and paper budgets. But this is oldschool anway.)

And yes, you are right: publishers were critical for the development of science. They were service providers, they did work for us. But this has changed a lot. A lot! Because of different interests (making money vs. publishing good research) they are more of a pain then anything else. Some examples:

- Proceedings of Formal Grammar published by Springer. We were supposed to deliver Camera Ready Copies. Involvement of the publisher: zero.

- The Handbook Semantics done by De Gruyter. A complete disaster. They sent the stuff to India for typesetting and got garbage back. All formulae screwed up. It took the authors weeks to get things right. Publishers are outsourcing work. To India and to us, who they are supposed to help.

- A collection of papers by Barbara Partee published by Blackwell-Wiley. This is a minor thing but the publisher just took the stuff and republished the papers. I read Anaphora and semantic structure recently and noticed that the typos are still in and even the source of the original paper is wrong: the editor of CLS 1980 was not A. Ojede but A. Ojeda. (In addition two typos and a crossreference from Section 6.5.1 to Section 6.5) A responsible publisher should at least check the information that is newly added to papers.

- This blog post discusses the multiple ways a paper of mine got broken by De Gruyter. They just do not do careful work.

- A particularly extreme example is documented here. It is an MIT dissertation that grew out of a target paper in a De Gruyter journal (2009). The target paper and the reply by the author in the journal was the basis of a MIT dissertation (2011). The target article and the response article were full of typos, which were taken over to the dissertation. Among other things there is the phrase “in other word” occuring 31 times in the PhD thesis. The thesis was published by De Gruyter in 2019 and it contains many of the original typos. What this shows is that nobody ever reads these papers on the publisher side. If we want to have high quality publications, we have to care for them ourselves. And this is what we do. But then why do we pay for a service we do not get? Compare this with copy editing for the journal of Linguistics or for the Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaften. In both cases we have experienced copy editors who know what they are doing (Ewa Jarowska and Susanne Trissler, the former one payed by CUP and the latter one payed by the DGfS [German Linguistics Society]).

3. The exorbitant price of journal subscriptions is partly the result of us all sharing our own publications (which is good for science) and not subscribing to journals anymore (which is good for our pocket book). “We” as academics have played and continue to play a role in the current price of journals!

This is an interesting thought. And yes, you are right, I once had a subscription to Linguistische Berichte and I cancelled it because I hardly read anything and the papers I do read I read as PDFs anyway. But I guess it does not explain why the profits of our big friends are rising every year. And exaggerating a bit: if the costs of producing a journal are zero it does not matter whether I read it or not. If they get the same amount of money for it as they got some decades ago, when real work was involved, they make a fortune. There is a talk by Klaus Mickus, who worked for Wiley. He explains what costs used to be involved in running a journal and what costs are involved nowadays. The costs are really almost down to zero, the profit rates for journals are 80%. (As somebody from the audience remarks: Only drug dealing can top this.)

And it is not just the profits that are rising, it is also the profit margins (2019 +2%). That is they get more money for doing less.

4. You assume that if journals were published by scientific society they would be cheaper. That’s true in Linguistics, but not in Psychology. Take Journal of Memory and Language (Elsevier) and Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition (publication of the American Psychological Association). The price of a yearly subscription for the latter for both individuals and institutions is slightly higher than the former! It would be possibly slightly lower for individuals (not institutions) if you are a member of the APA (their membership rate is complicated, it increases every year until the 8th year, I think, so it’s hard to tell), but you need a Ph.D. in Psychology or a related discipline to be a member and I don’t know that linguistics counts as related to psychology (I can make a case either way).

This is a complicated issue and it depends on the setup of societies. Societies like the Linguistic Society of America (LSA) basically get their main income from their journals. This is a setting grown over several decades if not centuries. This made it difficult for the LSA to switch (long discussions during the past years). The Deutsche Gesellschaft für Sprachwissenschaft always payed their publishers for publishing their journal. So, rather than paying the profit margin of the publisher, the society can publish with a service provider and save a lot of money. For example, Glossa is published with Ubiquity Press. Ubiquity Press is a commercial publisher taking care of typesetting, printing journal volums, putting papers online, indexing and so on. So there is a publisher involved. They also have a profit margin, which is ok (tell Joann), but it is not 37%. The crucial difference is that Ubiquity does not own the journal. They are service providers and they are replaceable. This is were the market kicks in (tell Joann). If we leave the brands (the journal names) to the publishers we are doomed. They can do whatever they want with us.

So, if societies charge more than Elsevier, their members should complain. They should ask what is done with the money. There are annual member meetings where such issues are discussed. They should ask whether the board has to meet several times the year and travel all over the country or the globe? They should ask whether the board has to stay in four star hotels. Scaling down is also good for the planet because it reduces our carbon impact.

In any case: Whatever the society does with the money, they get it for themselves. They do not give 37% to shareholders of some company.

And finally: There are good news on psychology journals: there will be a psycholgy version of Glossa run under Fair OA rules.

5. You assume open-access is always good, but to me the worst journals, ethically speaking, are not Elsevier or Wiley journals, but Frontiers since there the producer and institution have to pay an exorbitant price for publishing, which is the most unethical thing I’ve ever seen. I have asked my farmer to pay me so my animals and I can eat his products, clearly a great honor to him, but he didn’t go for it :).

I never said anywhere that all open access journals are good. There are predatory journals without peer review and there is rip off. As for Frontiers: These are the prices: Frontiers APCs. They are high. But Frontiers and the journal titles are not owned by societies. Frontiers is in part owned by the Nature Publishing Group, which is a Springer Nature daughter and Springer Nature is a merger of Science+Business Media and Holtzbrinck Publishing Group‘s Nature Publishing Group, Palgrave Macmillan, and Macmillan Education. Since the Holtzbrink imperium is privately owned, there are no business reports and we cannot find out to what extend Frontiers is owned by Holtzenbrink. This is Frontiers official statement:

2013. The Holtzbrinck Publishing Group (at the time owner of Nature Publishing Group and now majority shareholder of Springer Nature) makes an investment in Frontiers, enabling further growth of the Open Science vision. The two organizations run as independent businesses.

According to this webpage Holtzenbrink owned 30% of Frontiers in 2015:

SpringerNature is part of the Holtzbrinck-group, as we know. The latest annual report of Holtzbrinck-group from 2015 states an ownership of 30% on Frontiers (this is a minority stake; see Unternehmensregister). This stake could probably still be held by Macmillan Group (http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2015/05/open-access-publisher-sacks-31-editors-amid-fierce-row-over-independence or https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2015/01/20/macmillan-springer-some-lessons-to-learn-some-twists-to-watch/) which is also part of Holtzbrinck Group and potentially owner of the minority stake on Frontiers. This relationship and ownership are still unclear. But this will ligthen up when the next annual report of Holtzbrick-Group is published, IMO.

I hardly see any other (and easy) ways to check this realtionship by research in databases because Holtzbrinck Group is in private ownership which is not forced to publish annual reports and business statements like public listed companies. This makes it so hard to find out. And there are no official press releases wether by Holtzbrinck Group nor from Macmillian, which could have be of help.

In a blog post and interview with one of the founders of Frontiers by Richard Poynder you can read that the initial idea was to do without APCs, but this did not work out. Frontiers turned themselves into a for-profit publisher in 2008. As you can learn in the Poynder post, Nature Publishing Group (Springer/Holtzenbrinck) and Frontiers decided to remain silent about their relationship …

So the point is again: the brands have to belong to scientists and they have to be protected so that a sell-out is impossible.

6. Your use of the term Zombie Lingua is misleading. Journals do not belong to boards and editors, so Lingua remains Lingua after everybody resigned just as Language would remain the journal of LSA were the entire board and editorial staff to resign.

Yes, if people love each other very much they give nicknames to each other. The name is supposed to indicate that the journal is an empty shell, which it is. The complete board left, it was just the name of the journal left. It was an empty ghost, yes. Undead. Now, Elsevier filled the board again and it is a different journal. The number of syntax papers went down. It changed a lot and you are right Elsevier owns the name and can do with it whatever they want. Everybody who does not like this can call Lingua Zombie Lingua, as I can call Trump Donald “FakeNews” Trump or Donald “This is just a flue.” Trump.

7. There are areas of linguistics (e.g., psycholinguistics) where there is not much option but to publish in Elsevier, Wiley and the like (aside from the few APA relevant journals, most journals are published by for profit companies). Linguistics is also like this to some extant (point 2), but publication in refereed journals is not as critical in some areas of linguistics as a publication venue, on the one hand, and there are not as many linguists, on the other hand, so the number of journals that would be needed to make up for for profit journals is not as high.

Again: My post was about Lingua/Glossa and addressed to the HPSG list (mainly syntacticians). Do not publish in a for-profit journal if there is a community run alternative. By publishing in a for-profit journal you are strengthening the brand and make life more miserable/expensive for yourself. That there are no alternatives right now does not mean that this has to remain this way. The editors of any journal could just flip their journal and start a new independent journal.

And there is additional good news: there will be a new psycholinguistics journal that is scholar-owned and published under the FairOA standards: Glossa Psycholinguistics. Currently an editorial board is formed.

8. A minor point. Wiley is also (primarily?) a textbook publisher. Just thought I would mention it, as you may not know that (my son has used many Wiley textbooks), and of course textbooks is where the big bucks are. So, the CEO pay has to be understood in this context.

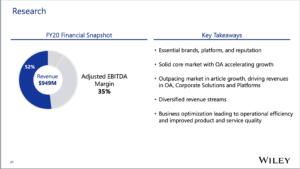

Yes, they get money from other business fields as well (as does Elsevier, who is in gun fairs). But according to their investors information of 2020 (p. 21) research publication is 52% of their business:

This video by Klaus Mickus explains how they make their profit in the journal market. So they get the margin at both places. And after all there should be changes in the textbook market too. The textbook publishers change their textbooks every two years. This makes it impossible for schools to keep them and reuse them. Do you need different textbooks for Latin every two years? What a waste! Remember our planetary boundaries? Furthermore the material cannot be adapted by teachers. What we need is open educational resources (OER). This would fix many of the textbook problems.

So, summing up: the journal brands have to be owned by scholars / by societies. This is the only way to protect our interests. Respective initiatives have to be supported. Publishers are ok, profits are ok, but publishers should be service providers and their profits should be related to the services they provide.

This blog post features one of my favorite typos: uniformed vs uninformed. I wonder where Joann the uniformed capitalist buys her uniform?

In China of course! I once heard that the US military had baskets made in China. Thanks for the typo. I guess I should leave it in. =:-)

You’ve said this: “I think that there may be other scholars with similar views, so it may be good to discuss them openly”

But you haven’t actually discussed the view in the comment at all. Wasn’t the point there that, as correct as you may be about open access publishing and for-profit journals, you shouldn’t be using not hiring people as the way to make this change happen? This post doesn’t really address that point at all.

There are many reasons why blacklisting is a terrible strategy. For starters, it is illegal. But it is also just bad leadership: there are a lot of people who are very sympathetic to the arguments against for-profit publishing, but who also don’t agree with blacklisting. Why would you want to alienate them all? Why can’t people support what you’re doing with open access publishing without having to blacklist potential hires? Why is the answer to everything in linguistics to just not hire anyone who disagrees? Anyone can make arguments like you’re making, and they are each as nonsensical as the next – here’s one: scholars who promote open access in linguistics are more likely to blacklist other scholars, which leads to a decrease in diversity of views and of backgrounds in teams. Diverse teams have been shown to be more productive and innovative. Therefore hiring scholars who promote open access in linguistics reduces productivity and innovation, so we should not hire scholars who promote open access in linguistics. This is as tenuous and nonsensical as your argument for not hiring people who continue to publish in Lingua.

Also, strategically, wouldn’t it make more sense to hire the people who continue to publish in Lingua and then work together towards a different way? After all, there are very few people who continue to publish in Lingua because they passionately believe that for-profit journals should continue in exactly the manner they currently do. Maybe you could take some time to try to understand what other reasons people would have for continuing to publish there? Maybe they just disagree with blacklists?

Either way, how is blacklisting individual candidates in hiring settings a good answer to any of the pressing issues that our field faces? If anything, it just polarises debate and divides people up even more than they currently are. We should be trying to unite and find good ways to handle structural problems like these together, not to turn on each other and punish junior colleagues individually for things that we ourselves did earlier in our careers.

“There are many reasons why blacklisting is a terrible strategy. For starters, it is illegal.“

I do not think so. I am working in Open Access and I need people qualified for this. Selecting appropriate staff is a normal process.

“But it is also just bad leadership: there are a lot of people who are very sympathetic to the arguments against for-profit publishing, but who also don’t agree with blacklisting. Why would you want to alienate them all? Why can’t people support what you’re doing with open access publishing without having to blacklist potential hires?“

I do not require that others act this way. I just wrote about things I do.

“Why is the answer to everything in linguistics to just not hire anyone who disagrees?”

This is a claim that may reflect a tendency in linguistics but does not apply to me. I hired many people working in frameworks I did not work in. The criterion for me is correct way of argumentation and intellectual honesty.

“Anyone can make arguments like you’re making, and they are each as nonsensical as the next – here’s one: scholars who promote open access in linguistics are more likely to blacklist other scholars, which leads to a decrease in diversity of views and of backgrounds in teams.”

I agree: a non-sensical argument.

“This is as tenuous and nonsensical as your argument for not hiring people who continue to publish in Lingua.”

I disagree.

“Also, strategically, wouldn’t it make more sense to hire the people who continue to publish in Lingua and then work together towards a different way? After all, there are very few people who continue to publish in Lingua because they passionately believe that for-profit journals should continue in exactly the manner they currently do. Maybe you could take some time to try to understand what other reasons people would have for continuing to publish there?”

Yes, I would like to talk to them. After all the paper appeared by now. I do not understand these authors and I do not see any reason to publish there.

“Maybe they just disagree with blacklists?”

Ha, this would be a funny reason and a made up one since what you call a blacklist did not exist when they submitted the paper.

“Either way, how is blacklisting individual candidates in hiring settings a good answer to any of the pressing issues that our field faces? If anything, it just polarises debate and divides people up even more than they currently are. We should be trying to unite and find good ways to handle structural problems like these together, not to turn on each other and punish junior colleagues individually for things that we ourselves did earlier in our careers.”

I am sorry: We did not do this ourselves. Nobody of us ever published in an Elsevier journal when the high-reputation editorial board of 31 researchers resigned and founded a new journal, which is intended to be the same journal but just open access.

“We should be trying to unite and find good ways to handle structural problems like these together”

I am doing this for almost 10 years with Language Science Press and the DGfS now. This includes work and talks with librarians, research founders and so on. A lot of people, linguists and others are involved with this. If you have further suggestions or want to join, you are most welcome. The amount of work happening in the back was/is enourmous and this is also one of the reasons, I will not hire anybody working against all this.